Scientists Predict Strong El Nino for 2015

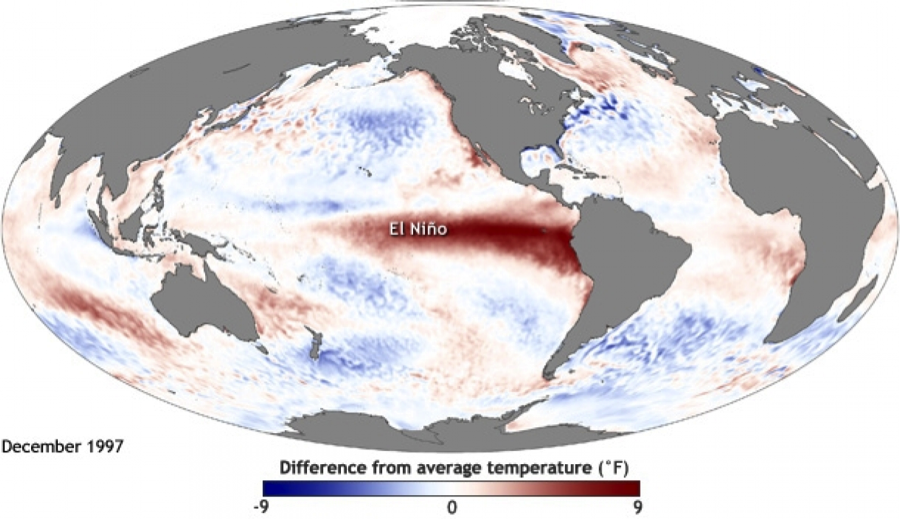

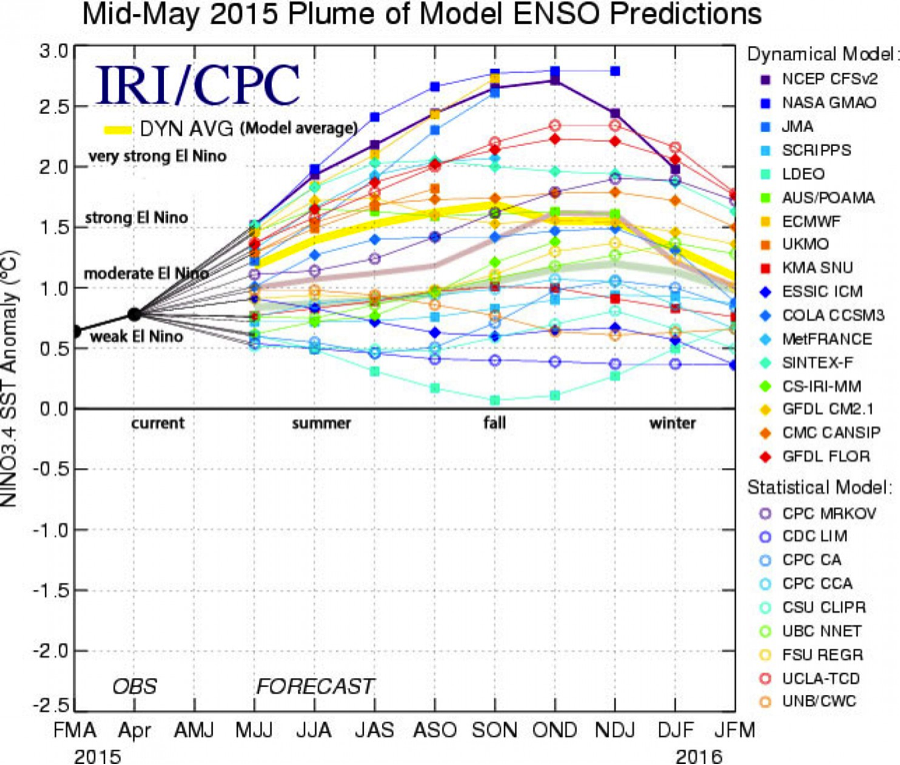

Government research centers and universities around the world are predicting that 2015 will bring a strong El Nino event. On NOAA’s ENSO blog, Emily Becker from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center, writes, “forecasters currently favor a ‘strong’ event for the fall/early winter”. The UK Met Office has also indicated that their models “suggest that this El Nino could strengthen from September onwards”. Some scientists are even warning that current conditions are reminiscent of the 1997 El Nino – the most severe on record. A report released by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology notes the abnormally warm sea-surface temperature observed in the Pacific Ocean over the last 2 weeks: “It is unusual to have such a broad extent of warmth across the tropical Pacific; this has not been seen since the El Niño event of 1997-98.”

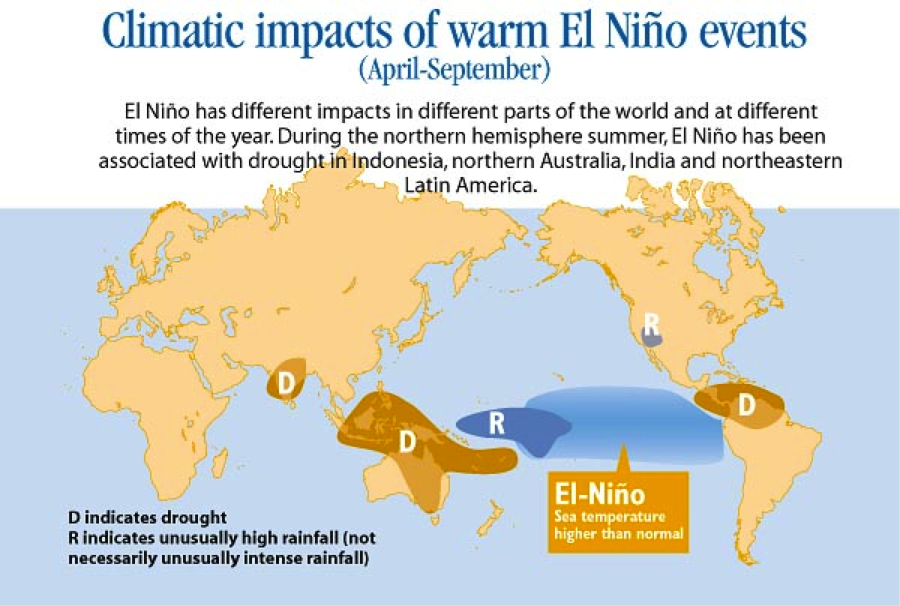

An El Nino event entails warmer than usual sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, which in turn impact weather systems around the world — triggering high temperatures, poor monsoons, and drought in Asia and east Africa, while causing heavy rains and floods in South America. Prof. Adam Scaife, of the UK Met Office’s Hadley Centre, said “With the current event, things like the Indian monsoon, tropical West Africa, the maritime continent [Indonesia], and Australian impacts are all appearing in current forecasts – all of those regions are at increased risk of drought.”

El Nino events occur approximately every 2 to 7 years as part of a natural ocean-atmospheric cycle, though some research suggests that extreme El Nino events will become more frequent under climate change. Additionally, this year’s El Nino event could prompt record-breaking global temperatures, as the first four months of 2015 have already been the warmest on record according to the NOAA and NASA.

A strong El Nino will be extremely hazardous for countries whose economies are highly dependent on agriculture, with crop failure and rising food prices creating food insecurity. The arrival of El Nino is most significant in regions where the main cropping season has just begun, such as in South Asia and West Africa; rain-fed rice production in South and Southeast Asia will be affected by the suppressed monsoon rains. In 2009, El Nino caused the worst drought in 40 years in India. In an interview with Reuters, K.K. Singh, the Head of the Agricultural Meteorology Division of the Indian Weather Office noted, “Crops like soybean and cotton are under El Nino watch for being sown mainly in rainfed conditions. El Nino looms large over soybean areas of the central parts and cotton belts of the western and the northern regions.”

A strong El Nino year is likely to disrupt food markets and elevate prices of staple food crops such as rice, coffee, sugar and cocoa. Some reports estimate that an El Nino event can cause tens of billions of dollars of economic damage to the Asia-Pacific region. In a country like Indonesia, where the agriculture, forestry, and fisheries sectors account for 18% of the GDP, historically, El Nino events have caused a percentage drop in the GDP and spiked inflation.

Forthcoming Monsoon Rains May Complicate Disaster Relief Efforts in Nepal

by Nina Horstmann

On April 25, a 7.9 magnitude earthquake struck Nepal. While reports about the extent of damage in rural areas are still trickling in, the UN currently estimates that over 8 million people have been affected by the quake and the Nepali government has accounted for over 7,000 fatalities. Since the quake, persistent aftershocks have triggered further avalanches and landslides, compounding the destruction. In addition to the capital city of Kathmandu, remote mountainous areas of Nepal have been particularly impacted, yet the ability of relief efforts to reach these areas has been impeded by the devastation.

The South Asian monsoon circulation brings rainfall to Nepal from June to September; during these 3 months the southwest monsoon brings more than 75% of the annual rainfall. The monsoon is critical for agricultural production in Nepal, which relies on monsoon rains for irrigation. According to the Nepali Department of Agriculture, the agriculture sector employs 2/3 of the population and makes up nearly 35% of the GDP.

Impending monsoon rains may frustrate relief efforts. Sienna Craig, a professor of Anthropology at Dartmouth University who has worked in Nepal for over 20 years, notes that monsoon rains will bring further challenges to the region, complicating access to clean water and triggering landslides that may frustrate reconstruction efforts. Pre-monsoon rains have already curtailed humanitarian aid in the region.

The seasonal monsoon brings heavy daily rains, as well as the threat of floods or landslides. Last year, torrential monsoon rains in Nepal caused multiple landslides and flooding; a particularly fatal landslide demolished an entire village east of Kathmandu, killing 156 people. Landslides may cause further fatalities, destroy makeshift shelters, and wipe out roads. Efforts by relief teams to reach remote regions may be hampered by rains that make it difficult for helicopters to fly and by landslides that bury roads in rubble.

Rownak Khan, the UNICEF deputy representative in Nepal, has stated that the forthcoming monsoon season is a concern, as deadly disease outbreaks could be triggered by the wet and muddy conditions. “Hospitals are overflowing, water is scarce, bodies are still buried under the rubble and people are still sleeping in the open. This is a perfect breeding ground for diseases,” said Khan. Another UNICEF spokesperson, Chris Tidey, warned that the prevalence of diarrheal diseases, respiratory illnesses, measles and cholera will soar during the monsoon season if people are living in the open during heavy rains. Thirteen UK humanitarian organizations that are involved in relief efforts in the country cautioned that the hundreds of thousands living outdoors will be vulnerable to the coming monsoon. Many are currently living in the open, camping outdoors or in makeshift shelters, because 130,000 homes have been flattened by the quake.

As medical expert Dr. Nikhil Joshi forewarns, “We often look at things in terms of death toll from a disaster. But that really only tells a fraction of the story.” Humanitarian relief to Nepal will be an ongoing trial, especially given the logistical difficulties of providing appropriate goods and services in a mountainous region that will soon be subject to the hydrological extremes of the monsoon season. People who are considering donating to the relief efforts might consider the particular efforts that have been recommended by the Yale Himalaya Initiative.

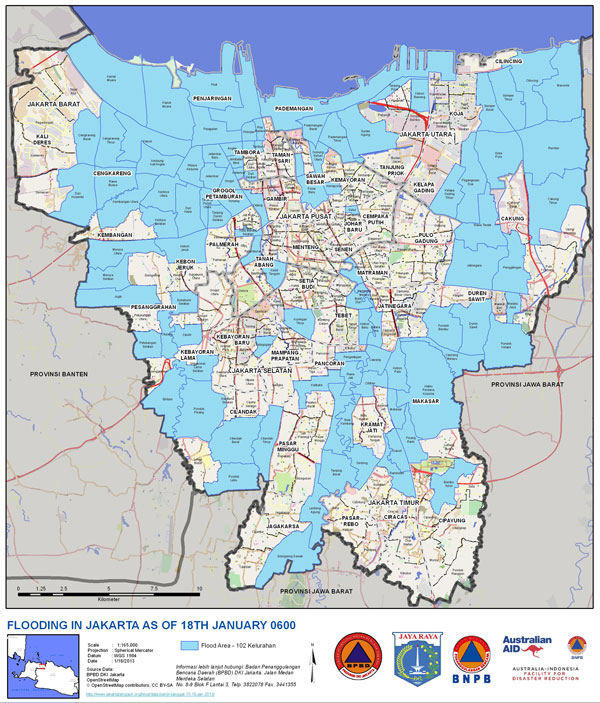

Monsoon rains induce flooding in Jakarta, Indonesia

by Nina Horstmann

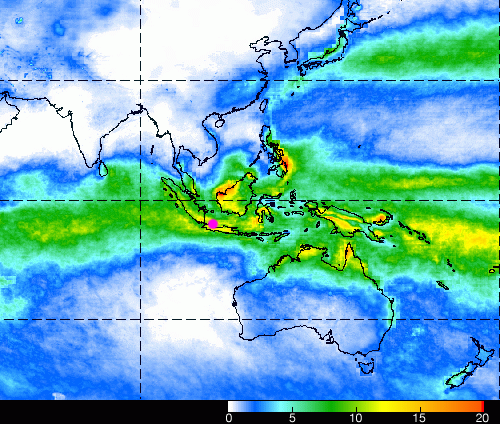

In early February, persistent rains triggered massive flooding in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, with floodwaters reaching up to 100 cm. Seasonal monsoon rains and the poor drainage of the low-lying capital city make flooding from late January to mid February an annual event. Other parts of Indonesia, such as the islands of Sumatra and Sulawesi, also experience seasonal flooding and mudslides, but these events are typically most severe in the capital. Around 240 square kilometers of central Jakarta lie below sea level, and flooding can become acute when heavy rain and high tides coincide.

Indonesia experiences extreme variations in rainfall between its wet and dry seasons because of the seasonal shifts in winds that constitute monsoons. Jakarta lies about six degrees of latitude south of the equator, and so receives the most rain in January, when the warmest, wettest air rises just south of the equator in the summer hemisphere. In fact, the island of Java, which is home to Jakarta, is right in the center of the Indian Ocean’s intertropical convergence zone – the near-equatorial band of precipitation that stretches around the planet.

The annual nature of the monsoon and related flooding in Jakarta complicates disaster response. In contrast to abrupt events such as a typhoon or tsunami, annual flooding is anticipated and gradual. Because of its expectedness, annual flooding enters the realm of the ordinary and does not prompt swift action or response. However, the Indonesian government still has not created a comprehensive system for addressing massive flooding, which annually brings the city of Jakarta to a standstill. Yayat Supriatna, a public infrastructure analyst, commented in The Jakarta Post that, “The city administration has to run faster by repairing the poor drainage system to allow a smooth flow of rainwater to all rivers; and also the pump houses, so that floodwater can be pumped out to the sea rapidly.” Because of the dense population of the Jakarta metropolitan area (according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, approx. 28 million in 2010), these annual flooding events affect millions of citizens.

Yearly, flooding disrupts transit and business activity, displaces thousands of residents, creates economic damage, and results in dozens of fatalities. Importantly, because the imbalance between precipitation and surface evaporation is expected to increase as climate warms, flooding might worsen in future decades. In 2013, Jakarta experienced an extreme year; a river burst its banks and flooding engulfed the Central Business District, resulting in hundreds of millions of dollars in property damage. In 2007, the human impacts of annual flooding were particularly dire, when 80 people were killed and an additional 200,000 were displaced due to severe flooding.

In order to prepare citizens and inform them of the extent of seasonal flooding, the Indonesian government is turning to the Internet and social media to disseminate forecast information. On its website, the Indonesian Agency for Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics (BMKG) provides a daily weather forecast as well as a map displaying the flood potential for different parts of the city. Additionally, the Natural Disaster Mitigation Agency (BPBD) and the Traffic Management Center of the Jakarta Police Department are using Twitter to release regular information of flood conditions in the city. A new website, PetaJakarta.org, also draws on the Twitter platform, using crowdsourcing to aggregate and map flood-related tweets.

PetaJakarta is an initiative run by BPBD and the SMART Infrastructure Facility at the University of Wollongong in Australia. The project reported that on February 9, a day which experienced massive flooding, their map pulled in around 800 flood-related tweets per hour and more than 12,000 users logged onto their site that day. The PetaJakarta mapping initiative allows BPBD to receive real-time reports, expediting their response to emergencies, and enables citizens to monitor flooding and traffic levels in their neighborhoods. Social media and Internet resources offer exciting new opportunities to disseminate advance forecasts and real-time weather and traffic conditions. This model could perhaps be extrapolated to other megacities in the tropics that are affected by monsoons and flooding.