Back in mid-April, several agencies made forecasts for how much total rain would fall during the first part of this summer’s monsoon season. Let’s look at how successful these forecasts were. We’ll stick to the May-July period, the first half of summer.

India’s Meteorological Department projected a near-normal monsoon, with 97% of normal rainfall (with a +/- 5% uncertainty range). The IRI at Columbia predicted an enhanced chance of wetter-than-normal conditions over much of South and Southeast Asia, with near-normal rain over most of Africa and dryness over only a few notable regions: Indonesia, the Yucatan Peninsula, and an elongated region over central/western Asia stretching from western China to Turkey and the Mediterranean. They also predicted a moderate chance of dryness over the western US:

Here’s what actually happened, at least according to one rainfall estimate from NOAA’s CPC: the biggest rainfall anomaly is the very large wet anomaly over Vietnam, Myanmar & Bangladesh (see below graphic, which shows a 3-month period ending in early August instead of end of July because that’s what’s easily on hand). There was flooding in Vietnam, in part due to Tropical Depression Son Tinh, which caused deadly floods and landslides, and in part due to heavy rains in June. A dam collapsed in Laos, flooding displaced 120,000 people in Myanmar, and there were floods and high river levels in Cambodia and Thailand, according to FloodList.com. The seasonal forecasts weren’t wrong in these regions (see the light green shading in the IRI forecast above), but this is a good example of how little information there is in a metric like “40% chance of above normal rainfall in Southeast Asia”. Or, a reminder that “above normal rainfall” could mean torrents. And of course it is also important that most seasonal forecasts are probabilistic, so a single season can’t prove them right or wrong; nevertheless, making these sorts of comparisons is a good way of keeping up with what actually happened in monsoon regions and how forewarned we were.

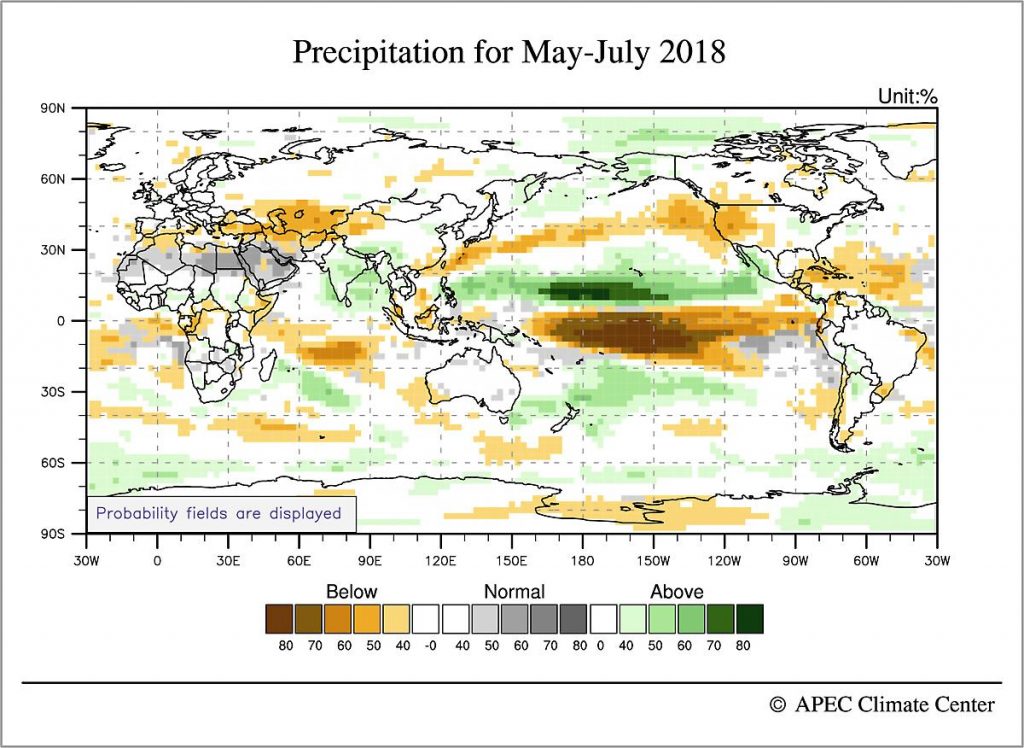

Elsewhere, the Sahel and eastern Africa had a wet early summer, with deadly floods in Algeria, Liberia, Kenya, and other countries, according to articles aggregated by FloodList.com. Such widespread wetness wasn’t predicted in the IRI forecast or the forecast from the APEC Climate Center in Korea (below), and neither was the dryness that occurred in northern South America. The eastern US got a lot of rain, and the western US was near normal (at least according to this precipitation estimate), all in contrast with the seasonal forecasts. The APEC forecast was overall quite similar to that of the IRI in most regions, although it also shows the oceanic rainfall anomalies which provide a useful connection with what’s going on with the global-scale circulation (this is their May-June forecast issued in late-April, 2018):

Since the figure for actual rainfall that we showed above only included land regions, let’s compare this with the observed outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) for May-July (with about a one-week lag again, because it’s what is easily on hand):

The APEC forecast provides a decent reproduction of the rainfall/convective activity in the Pacific Ocean, with alternating wet and dry bands in the Pacific in roughly the right positions. The extreme wetness of Vietnam and Myanmar don’t show up in the OLR anomaly. In the above OLR map, the western US does look dry, unlike the precipitation anomaly plot shown earlier—although the very active wildfires in parts of the western US would seem to suggest dry conditions, NOAA has said rainfall in the North American monsoon has been normal, and many California reservoirs are near normal (72% to 130% of their historical average).

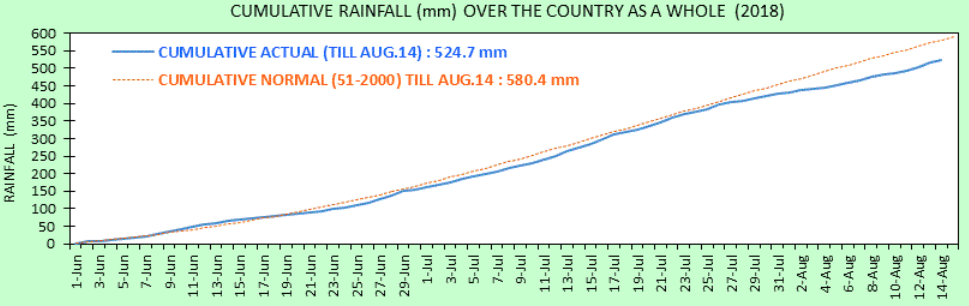

In summary, the clearest forecast miss, at least in monsoon regions, was in Africa where the Sahel had a wet May-July period that was not forecast by APEC or the IRI. The forecasts of the South Asian monsoon are harder to judge because both positive and negative anomalies exist. India as a whole received below-normal rainfall through the end of July, and has gotten drier since then (the below image is taken from the India Meteorological Department’s website):

But India is also a sobering example of regional heterogeneity, as it often is: even though the country as a whole is in a nearly 10% deficit compared to a normal monsoon year, the Times of India reported 774 dead from floods. These deaths were spread across the country in seven states. Even though the flooding in Kerala near the southern tip of India has gotten a lot of attention, there were about 170 deaths in the northeast state of West Bengal, 171 deaths in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh (bordering Nepal), and 139 deaths in the central state of Maharashtra. Some of these were caused by floods associated with westward-propagating monsoon lows or depressions. India’s environmental news site Mongabay had an interesting article on the floods and drought that are occurring concurrently in this year’s monsoon.