Home » Blog

Category Archives: Blog

India issues first monsoon forecast of season; Mexico no longer wet?

India’s first forecast for the 2018 summer monsoon season was just released, and it is for a near-normal amount of rainfall over the country as a whole. In particular, based on their statistical model and their relatively new numerical model, they are predicting 97%±5% of the historical average. More details on the India Met Dept website (find the link in the right-hand bar of scrolling news).

They also cite a ‘low probability’ for deficient rainfall, meaning that there is a 42% chance the rainfall will be in the ‘normal’ range of 96-104% of the long-term average. It’s interesting that their probability breakdown gives a higher probability of low rainfall (44% chance) than of high rainfall (14% chance), but it’s unclear whether their statistical model has enough skill for such subtleties to be meaningful.

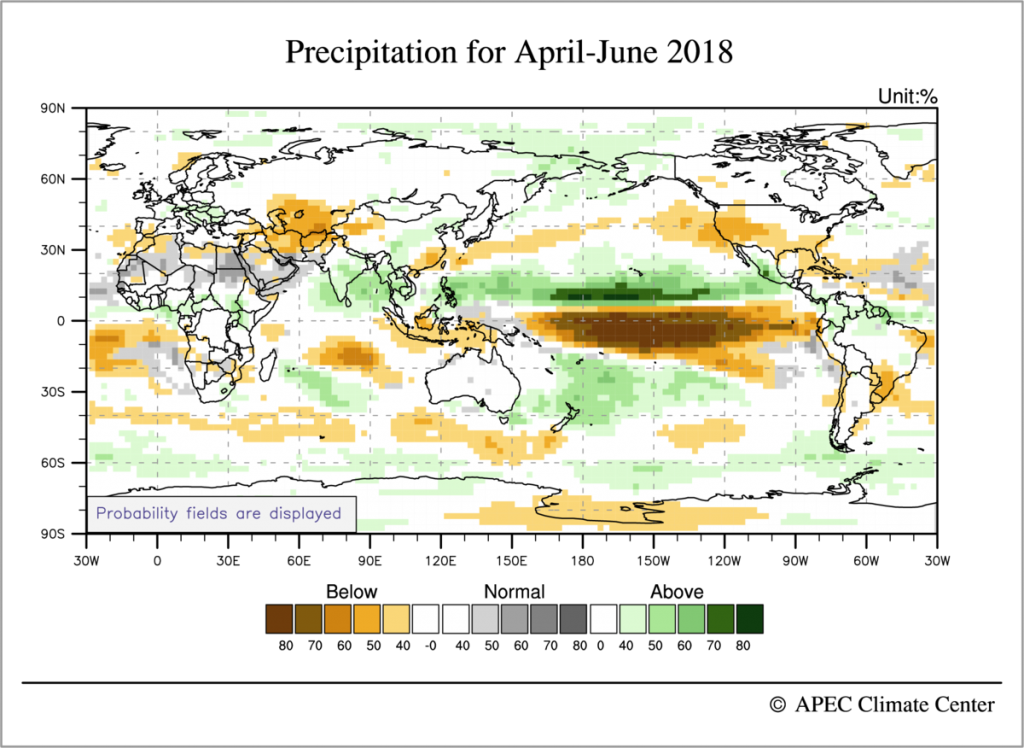

Columbia’s IRI also updated its global seasonal forecast on April 15, and the only notable change for monsoon regions is that Mexico is no longer forecast to be wetter than normal during the spring/early summer. Mexico didn’t have anomalously high rainfall in April thus far, and it doesn’t look like the current weather models are forecasting high rainfall there over the next week, so this actually seems like a change in the spring forecast:

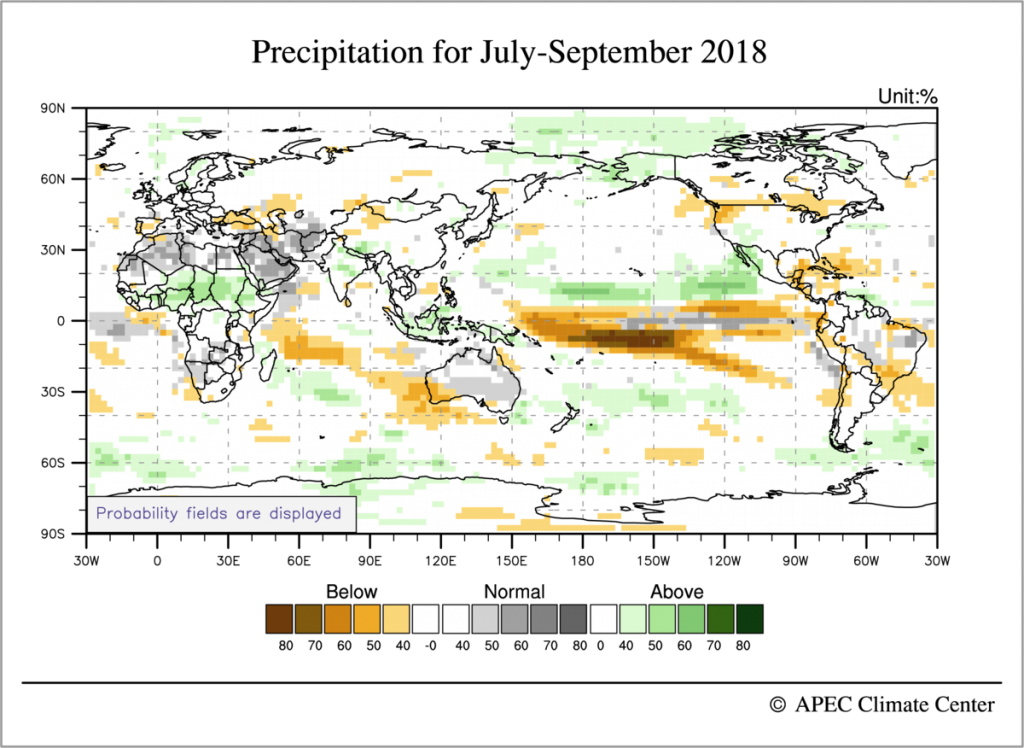

Combined with their July-Sept forecast, this makes it look like India’s country-averaged, seasonal-mean rainfall might indeed be normal, but only because the country will be wet in the northeast during early summer and dry in the south during late summer:

The ENSO forecasts still have La Niña transitioning to a near-neutral ENSO index, but this again is made up of warmer water in the north Pacific and Atlantic, and relatively cold water south of the equator in both of those ocean basins. Given research showing how the tropical rainfall maximum can shift north-south into the hemisphere with the warmer ocean, this helps justify the idea that Africa may be wetter in the northern parts of the Sahel and drier in the south, and that India may also be wetter in the north and drier in the south.

Forecasts of the 2018 summer monsoon

The summer monsoon season will soon be starting in South Asia, northern Africa, and north America, so it’s time to check in with forecasts of seasonal rainfall. India will release its first monsoon forecast in a week or two, and a number of the seasonal forecasts discussed below will be updated in the next week, but it’s nevertheless a good time to take a first look at what might be happening.

IRI/Columbia University is predicting a wet early summer in the Philippines, Southeast Asia, and western Mexico, and a wet late summer in much of Africa (especially East Africa):

The APEC climate center in Korea has many of the same features; because their maps show oceanic rainfall, the wet anomalies over Mexico and the Philippines are more clearly seen as part of a northward shift of the East Pacific ITCZ:

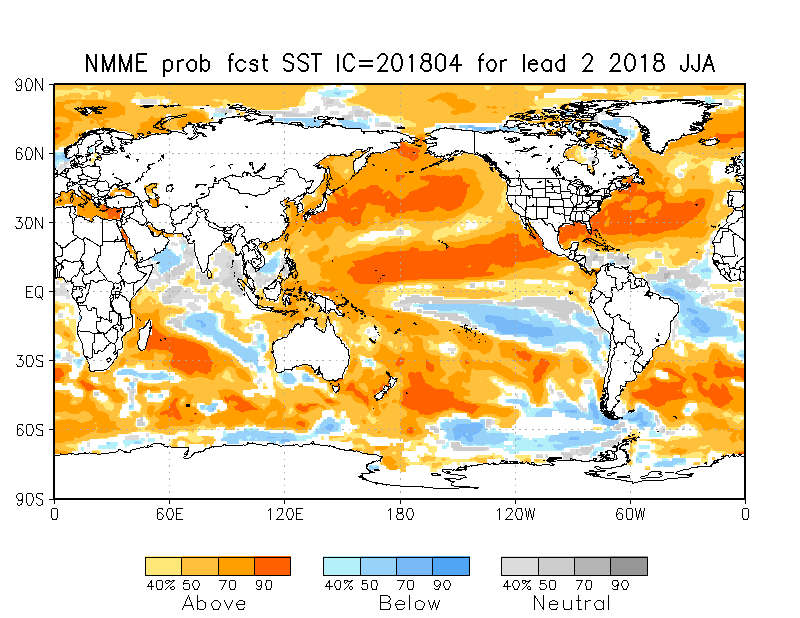

This northward shift of the East Pacific ITCZ isn’t a classic La Niña pattern. Most of the models are actually forecasting a transition from La Niña to El Niño during summer, but this seems to occur with the cold SST persisting south of the equator in the East Pacific while the northeast Pacific warms, producing that northward shift in the ITCZ that may bring wetness to Mexico, the Philippines (and maybe even SE Asia?). Here are the SST forecasts from the North American Multi Model Ensemble:

The Australian BoM provides a nice overview of all the large-scale climate modes: ENSO is nearing neutral, as is the Indian Ocean Dipole. The BoM model is predicting a negative IOD during June (i.e. cooler SST in the western Indian ocean relative to the east), but there seems to be a fair amount of disagreement in models on this — the NMME forecast shown above looks to be a near neutral for JJA, while even the BoM page shows that only 2 out of 6 models forecast a clear negative IOD phase for June.

Links to the forecasts discussed above:

http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/overview/influences

http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/#tabs=Indian-Ocean

http://www.apcc21.org/ser/outlook.do?lang=en

https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/seasonal-climate-forecasts/

Drought continues to threaten Horn of Africa

Ongoing drought and conflict in the Horn of Africa have left 14.4 million people in need of food assistance in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. Drought conditions in the region have led to crop failures, weakened agricultural sectors, water shortages, and widespread hunger requiring international assistance and humanitarian action. The region has a history of severe weather, drought, and famine — a famine resulted in the deaths of 250,000 people in 2011, and water shortages and stunted agriculture have threatened the country since.

Seasonal rains arriving in mid-April and spreading throughout the Horn of Africa in May bring hope for relief from the drought’s most severe effects, although these rains also pose a threat to some living in the region. According to Relief Web, the rains have primary affected the “central, northwestern and southeastern Kenya, Uganda’s Karamoja region, and southern and central Somalia.” In Kenya, heavy rains have resulted in flooding and landslides. April rains also caused flash flooding in Somalia, but the IGAD Climate Prediction and Applications Centre has predicted that the country will see minimal rainfall in May.

Although seasonal rainfall has arrived in these areas, it is unlikely that it will be sufficient to draw the region out of its long and severe drought. In fact, sources predict that overall rainfall will be below-average this season. According to the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s Climate Prediction and Applications Center (ICPAC), “What makes the current drought alarming in the Equatorial Greater Horn of Africa region is that it follows two consecutive poor rainfall seasons in 2016, and the likelihood of depressed rainfall persisting into the March-May 2017 rainfall season remains high.”

If rainfall does not increase, the agricultural and economic impacts of the drought will continue to affect the region. Although large-scale humanitarian relief efforts led by organizations such as the World Food Programme (WFP) have had a positive impact, they have been insufficient to reach all those who are suffering in the region’s drought-affected areas. Funding deficits, the dangers of conflict areas, and roadblocks restricting travel have all hampered aid efforts. Meanwhile, 10.7 million people face severe hunger in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. Those most at risk include nomadic pastoralists, who travel throughout the region relying on livestock and agriculture for survival.

Droughts have also led to health crises in the region. According to UNICEF, 3.4 million children are at a high risk of contracting measles in the drought-affected areas of the Horn of Africa today. Unfortunately, seasonal rains have the potential to exacerbate health risks like these. Rains can lead to cold weather and the spread of diseases like cholera, both of which are particularly threatening to those whose immune systems have been weakened by malnourishment. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 25,000 have been infected by Cholera in the country this year. As health systems in the region are weak, many rely on the care of international organizations and non-profit organizations for treatment of these diseases.

Ethiopians, Somalis, and Yemenis have been displaced as a result of the crisis, many traveling to settlements and refugee camps throughout the region. In Somalia alone, there have been over 650,000 drought-induced displacements. The country is home to roughly 220 settlement sites, and of these, more than 40% have reported food shortages and only 31% are within a 20 minute walking distance of a fresh water source.

The Ethiopian government currently houses close to 800,000 displaced persons from surrounding countries, including those from Ethiopia escaping drought and conflict. One settlement can house between hundreds and thousands of displaced persons, many of whom face severe malnourishment or require medical attention.

International organizations such as Oxfam International argue that climate change has exacerbated both the drought and humanitarian crisis the the Horn of Africa region. Oxfam cites a trend of increasing temperatures in the region since the 1980s, pattern of cattle deaths, and severe weather patterns as evidence of this trend.

Forecasts Issued While India Awaits 2017 Monsoon Season

As India anticipates the beginning of this year’s monsoon season, forecasting agencies are beginning to issue their predictions for summer rainfall. Weather forecasting agency Skymet has anticipated a slightly drier than usual monsoon season for the country as a whole, at 95% of normal (note that drought typically occurs when rainfall decreases to 90% of normal). The Indian Meteorological Department’s (IMD) 2017 monsoon forecast prediction is almost exactly the same, though they classify this as lying within the range of average rain levels.

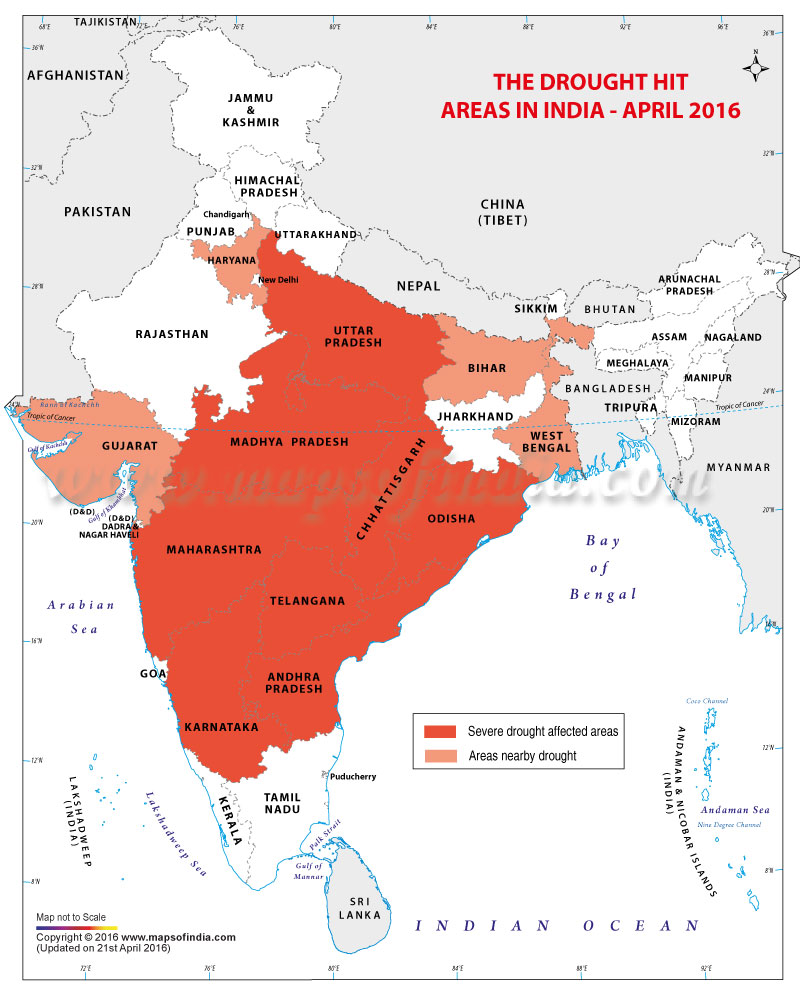

IMD Director K. J. Ramesh announced last week that rain levels are forecast to be 96% (with an uncertainty of +/- 5%) of the country’s long-term average. Rainfall will differ across the country, with the western portion of the country forecast to experience rainfall deficits. As the country saw its warmest year on record in 2016 with only 91% of its long-term average rainfall, Indians now await the monsoon’s crucial rains.

Other forecasting centers make slightly different predictions. The IRI at Columbia University predicts a likelihood of above-normal rain over the northern part of peninsular India with below-normal rain to the south. The Asia-Pacific Climate Center predicts near-normal rain until June, then dryness over the western parts of the country from July onward.

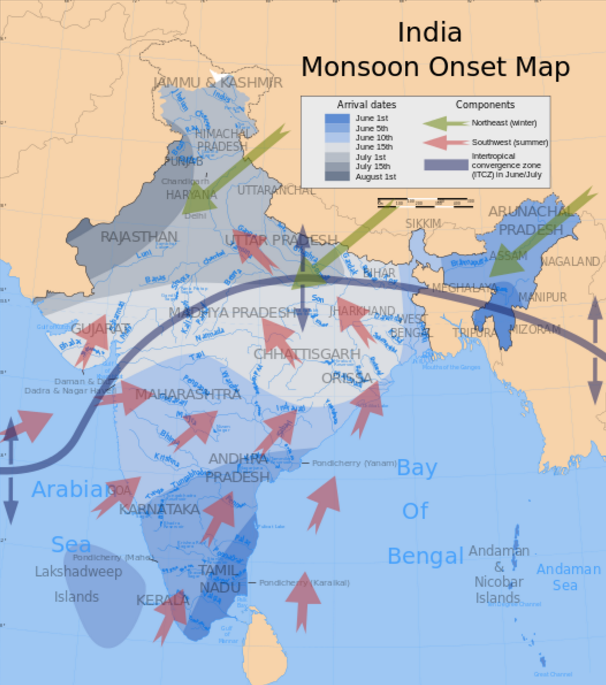

The South Asian monsoon, which affects India and several nearby countries, is a prominent atmospheric circulation system bringing crucial rainfall to the region annually. Rains are usually heaviest in June and July, although the monsoon can begin as early as May and end as late as September, depending on the year. Summer monsoon winds travel through the country from the southwest, bringing an average of 75% of the country’s annual rainfall.

Much of April saw high temperatures and minimal pre-monsoon rainfall, but temperatures recently began to drop with the start of some pre-monsoon rains. This is welcome relief to March temperatures that exceeded 40 degrees Celsius in some Indian cities, with heatwave conditions having developed across northern India. With temperatures 5-6 degrees Celsius above average in some regions, Indians feared the start of another exceptionally warm summer.

March and April heatwaves were the result of winds traveling south from Pakistan. They affected cities like India’s Nashik, which just experienced its hottest March in over a decade. The IMD had predicted that the heat would last through April, bringing record-breaking temperatures to already-warm regions. K Sathi Devi, head of the IMD’s National Weather Forecasting Center, has predicted high spikes in temperatures to continue throughout the monsoon season.

Below-average rainfall is expected to affect the Indian regions of Goa, Gujarat, Karnataka, Kerala, Konkan, Maharashtra, and Tamil Nadu. Several of these states are included in the eight Indian regions facing drought conditions this year. Jharkhand, Odisha, and West Bengal, on the other hand, will likely experience normal rainfall levels through the monsoon season. Skymet CEO Jatin Singh predicts that rainfall will be heaviest for the first month of the season.

If sufficient rains do not arrive, warm temperatures and drought conditions can become dangerous. Already this year, six Indians died in a heatstroke in the state of Odisha. As reported by the IMD, over 700 died as a result of weather conditions last year in the country.

Below average precipitation could also have agricultural and economic consequences for the country. Although India is home to over 15% of the world’s population, it has just 4% of the world’s water resources. Additionally, as only 35% of the country’s agricultural land is irrigated, a large portion of the country depends on rainfall for farming. Both crops and livestock that are crucial for subsistence farming and economic health, particularly in rural areas, rely on the Indian monsoon.

During Californian floods, Mexico becomes unusually dry

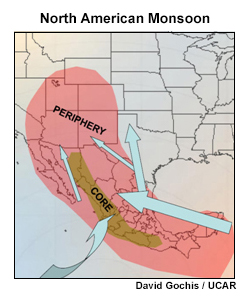

While news headlines have focused on the atmospheric rivers that flooded parts of California this winter, few have noticed that the North American monsoon region has become unusually dry.

Each year, the North American monsoon brings crucial rainfall to western Mexico and the southwestern United States. The monsoon has a significant impact on the lives of the 12 million people living within its reach, as it accounts for a large portion of the annual rainfall necessary to sustain life and support agriculture in the region. Specifically, the North American monsoon brings 60-80% of the northwestern Mexico’s annual precipitation, and 35-45% of the annual precipitation of Arizona and New Mexico.

The North American monsoon begins in southern Mexico around June of each year. Heavy rainfall then expands north through the mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range. When the monsoon arrives, weather conditions change from hot and arid to cool and wet. This can occur as early as June in Mexico or July in Arizona or New Mexico. As the monsoon progresses, rainfall tends to intensify and dangerous effects of hydrological extremes become more likely. The most severe rainfall usually occurs in the Gulf of California or Sierra Madre Occidental maintain range, where average monthly rainfall is 12 inches. Here, heavy rains transform “near desert conditions to those typical of a tropical rain forest within several weeks,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. When the monsoon season has concluded, parts of Mexico and the western United States experience a mid-summer drought of varying length and severity.

Although the heaviest rains are usually concentrated in these two areas, monsoon storms are dispersed throughout the region and their severity often depends on a number of influencing factors changing from year to year. These include the position of waves in the midlatitude jet stream and ocean surface temperatures — both influence rainfall patterns and severity. The nature and magnitude of each year’s monsoon significantly affects agriculture and farming, the health of ecosystems, and the likelihood of wildfires in the western North American region.

So far this year, the Western U.S. has seen above-average rainfall, and all of North America outside of the Pacific Northwest has seen anomalously high temperatures. In Phoenix, Arizona, for example, rain levels and temperatures exceeded monthly averages by 0.32 inches and 2.2 degrees Fahrenheit, respectively. But while California has been receiving significant media attention for its torrential rainfall and floods, droughts in western Mexico have been developing.

Western Mexico is currently experiencing a rainfall deficit. Although experiencing heavier than usual rains this past summer, the region has been unusually dry through the winter months. The North American Drought Monitor has classified this region as “Abnormally Dry”, the result of a 40 millimeter rainfall deficit. While this deficit does not yet constitute a widespread drought, severe drought has started to occur in isolated regions such as the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

Oaxaca’s Isthmus region is currently facing its worst drought in five decades. Drought conditions have resulted in low agricultural yields, economic woes, and severe water shortages throughout the region. The Isthmus accounts for over half of the state’s cattle production, and already, the drought has led to the deaths of over 1,500 cattle due to starvation or diseases caused by malnourishment. Water levels are also exceptionally low, with the region’s largest reservoir at only 16% capacity. The reservoir deficit has led to concerns among the 800 local fishermen working in the area who are concerned about the drought’s effect on their incomes and families. The country’s National Water Commission has responded to the low water levels by declaring a state of emergency in 27 of the state’s 42 municipalities.

After drought, flooding devastates Bolivia and Peru

Heavy rains have drenched central South America over the past month, causing dangerous flooding in Bolivia and Peru. As a result, lives have been lost, houses have been destroyed, and crops have been threatened in both countries. The states’ governments have been forced to deploy emergency assistance to bring aid to those threatened by the extreme weather.

In Bolivia, severe downpours have surprised unprepared towns and villages. In January, the Bolivian town of La Paz received 37 mm of rainfall in two days. This accounts for 25% of the city’s average annual rainfall, at 137 mm. Last month near Villa Pagador, just 10 minutes of heavy rain caused rivers to overflow, resulting in flash flooding. The country also faced flooding following violent thunderstorms in December, which resulted in the deaths of eight Bolivians.

These floods follow a period of severe drought. In fact, in 2016 Bolivia faced the country’s worst drought in 25 years. Water shortages in the country’s highlands led to both political and economic disputes, as residents fought for access to clean, safe water. The drought grew so extreme in November, particularly in La Paz, that a state of emergency was declared. Today, post-drought flooding makes the country vulnerable to mudslides and landslides.

Peru is also experiencing the devastating effects of extreme weather including flooding, landslides, and mudslides. Since the 30th of January, over 90,000 Peruvians have been affected by flooding in the country’s Piura region. On the evening of January 30th, heavy rains in Piura lasted for 30 hours straight. As a result, two people died and over 2,000 others were affected. By February 7th, flooding had displaced over 2,500 residents in the region.

In the nearby region of Lambayeque, nearly 60,000 have been affected by flooding and more than 1,800 homes have been destroyed. The region’s La Leche river has overflowed, threatening residential areas, agriculture, and business in the area. Heavy rains have traveled throughout the country, killing five Peruvians in the southern state of Arequipa. The most affected areas include Arequipa, Huancavelica, Ica, Lima, Moquegua, Piura, Puno, Tumbes, and Ucayali.

Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski has responded by pledging to provide emergency services, fuel, and water pumps to Lambeyeque and other affected cities. Additionally, the Peruvian government has declared a 60-day state of emergency in Tumbes, Piura, and Lambayeque.

Extreme weather in Peru has also affected agriculture and farming. In the village of Ayacucho, over 180,000 alpacas have died from starvation, the result of a cold weather front accompanying rains in the region. Low temperatures had caused the fields where the animals graze to freeze over. Families in Ayacucho, who depend on alpaca farming for survival, are fearful of the additional threats future storms may bring. Additionally, floods have destroyed 12,000 hectares of agriculture in the country. These include crops of alfalfa, beans, oats, potato, and quinoa.

South America saw the impact of severe flooding in 2016, as well. In October, heavy thunderstorms led to a massive landslide in the valley of Volcan, Argentina. Homes were destroyed and over 1,000 were evacuated from the area. The landslide interfered with the “Dakar Rally”, a race traveling through Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina.

Health, hunger concerns as East Africa faces severe flooding

As of August of this year, severe flooding after prolonged drought has affected more than 200,000 people in West Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan. These countries have faced heavy flooding since early June, mainly affecting the Sudanese states of Al Gezira, Kassala, and South Darfur. At least 98 people have lost their lives in the flooding this season, with numbers expected to rise as the crisis continues.

This flooding has occurred in the midst of violent conflict and humanitarian crises in Sudan and South Sudan. In South Sudan alone, nearly 2.5 million people have been forced by the conflict to flee their homes. Today, nearly 4.8 million are in need of humanitarian assistance due to the South Sudanese conflict. While the vast majority of need for humanitarian assistance in Ethiopia, Sudan, and South Sudan is a result of conflict, severe hunger and malnutrition, health crises, and poor infrastructure are also sources of need. Flooding has only further complicated efforts to deliver this aid. Humanitarian agencies and providers of aid are now struggling more than ever to deliver aid to the countries’ most needy.

This flooding occurs immediately after a multi-year period during which Ethiopia faced its worst drought in five decades. Drought conditions have devastated agriculture in the region and raised food prices, contributing to food insecurity for more than 10.2 million Ethiopians. South Sudan faces a comparable food crisis with a quarter of its population, or 2.8 million, in need of food aid this year. Droughts and rising temperatures have hurt harvests of rice, sorghum, soybean, and wheat in the area. As 40% of the East Africa region’s gross domestic product depends on agriculture, these crop shortages can also take a serious toll on the economic health of the region.

Although rains in some areas alleviate the threat of the region’s lasting drought, flooding also poses a serious risk for agriculture. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, heavy rains and flooding threaten crops in Sudan and South Sudan by waterlogging fields and destroying crops in the region. The flooding of the Gash River on the border of Eritrea and Ethiopia, for example, has flooded entire farming villages, destroying crops and homes. Ethiopia’s Blue Nile is also a flooding danger, according to UN aid agencies.

This year’s flooding has also led to a serious cholera outbreak in South Sudan. South Sudan’s Minister of Health confirmed the outbreak in July, announcing that the country’s National Public Health Laboratory had found Vibrio Cholerae Inaba (Cholera) in several sewage samples taken earlier that month. By July 26th, 391 cholera cases had been reported in the country, with 17 resulting in deaths. UNICEF’s Cholera Task Force is now in full operation in the country working to improve sanitation, health service access, and water quality in the country.

In the state’s capital, Juba, escalated violence has led to a breakdown in service provision, making cholera containment even more difficult. So far, cholera deaths have occurred in the states of Eastern Lakes, Imatong, Jonglei, Juba, and Terekeka. International non-governmental organizations including the World Health Organization, UNICEF, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and others are now working to build up health capacities in these and other states to quell the rise of cholera and other infectious diseases made more dangerous by flooding and its effects.

Delayed Monsoon Hits India

By Harland Dahl, from New Delhi

With over a third of India’s states experiencing severe water crises and many others facing a blistering heat wave, India’s monsoon season couldn’t have come soon enough. The southwest monsoon supplies India with 75% of its water for the year. This year, drought conditions have been severe enough to require some Indian cities to stockpile food and water from other regions. In Maharashtra’s Latur, for example, water trains have been used to bring drinking water to thirsty populations from over 300 kilometers away.

Source: SkyMet Weather

The strength and timing of monsoon season can have an effect on India’s economy, as well. As agriculture is the main source of income for roughly half of India’s population, a strong monsoon season can mean lower prices for food and crops, reduced inflation, and provide economic stability for India’s farmers and farming communities.

Although droughts have become increasingly frequent in India over the past few decades and parts of India currently face water crises, this year’s monsoon may be heavier than usual. Earlier this year, the India Meteorological Department predicted that, on a national level, the summer’s monsoon would bring above-average rainfall. Although the monsoon’s late arrival in mid-June temporarily exacerbated water shortages in parts of the country, it’s above-average performance has been a relief to many. So far, this season’s total rainfall has been 1% higher than average. Monsoon rains were 35% above average in the first week of July, and in the northwest of the country, rainfall went up to 57% above normal rates.

Monsoon flooding has primarily affected northern, central, and western India. Rains have been particularly heavy in the states of Madhya Pradesh, where 15 people were killed as a result of heavy rains, and Uttarakhand, where upwards of 40 people died after flash floods and the landslides they caused. In the northeastern state of Assam, flash floods have displaced families and prevented movement between villages. In the state’s Jorhat district, for example, almost 20 villages have been cut off by flooding.

While some areas have been receiving above average rainfall, others still face a rainfall deficit. Uneven monsoon coverage has resulted in a 17% rainfall deficit in the country’s eastern region, and certain states have even higher deficits. The Kutch region, for example, has a rainfall deficit of 84%. The state of Gujarat has taken steps to make up for a deficit of 58% by distributing supplies of drinking water and cattle fodder to its driest areas.

Source: Getty Images

The World Resources Institute estimates that half of India’s 1.3 billion people experience severe water stress. After two years of weak monsoons and dry, hot summers, many areas face droughts. Water shortages have created “water refugees”, forcing some families to relocate in search of safe drinking water and others to travel as many as 9 kilometers to reach water supplies. Even in some areas facing only mild shortages, like rural Uttar Pradesh, it is common for drinking water to be contaminated by pollution from factories or human waste. It is estimated 130 million Indians live in areas where groundwater is contaminated by at least one dangerous pollutant such as arsenic or nitrate. In areas like these, dry seasons and water shortages mean that many have no option but to drink contaminated water. Residents here look forward to a the year of above-average rainfall predicted by the India Meteorological Department.

India’s water supply has been steadily declining over the past few years, and Prashant Goswami, Director of the CSIR National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies in New Delhi, estimates that Delhi could exhaust its water supplies in less than 1,000 years. Despite low supplies, India continues to lose water through its agricultural exports each year. India accounts for 2.5% of global agricultural exports, and is estimated to have exported 25 cubic kilometers of water embedded in exports in 2010, alone. This estimate doesn’t include the water used to grow grains and rice, and is enough to supply water for almost 13 million people.

Water shortages, dry weather patterns in some areas, and heavy flooding in others, make accurate weather prediction tools important for preparation for future extreme weather in India.

Statistical models have been used by India to predict monsoon rains since the 1920s, when India was under British colonial rule. Although these statistical models have been reinvented multiple times since then, some experts have questioned the accuracy of these models, which use temperatures, wind patterns, El Niño and La Niña, and Ganges flows to predict weather patterns. This year, the India Meteorological Department is investing $60 million into an improved forecasting system, which will be based on U.S. dynamical weather prediction models. The new system, which could increase the accuracy of the IMD’s predictions by 15%, should be introduced by 2017.

Millions in Asia vulnerable to extreme weather threats

By Harland Dahl

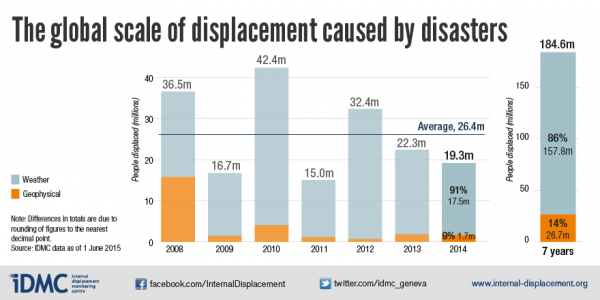

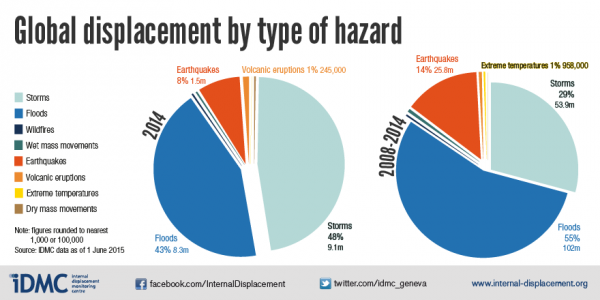

Over 19 million people from 100 countries were forced to relocate in 2014 due to the effects of natural disasters including drought, soil degradation, typhoons, cyclones, and other extreme weather events, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre 2015 Report. The International Organization for Migration has estimated that by 2050, there will be as many as 200 million climate migrants globally.

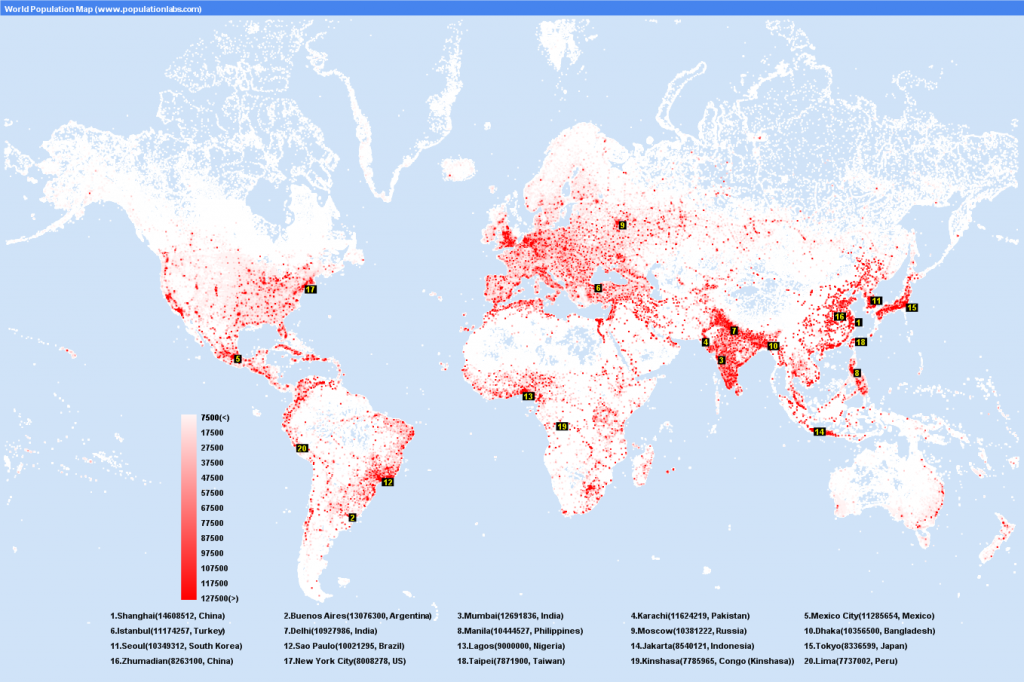

In Asia, alone, it is estimated that over ten million people were displaced by climate-related extreme weather events in 2011. These numbers include groups like the 200,000 Bangladeshis who are displaced by river erosion each year, or residents of small islands such as Kiribati and Nauru who are threatened by changing environmental conditions and rising sea levels.

In global terms, Asia and the Pacific is the region most affected by extreme weather both in terms of people affected and number of natural disasters occurring in the region. Research from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) cites climate variability as a main driver of migration patterns and displacement within South Asia. Globally, 80% of countries with the largest populations living in low-elevation coastal zones are located in Asia and the Pacific. The Bank estimates that one third of the population in South Asia lives in areas at risk for climate-change-induced sea level rise.

Asia and the Pacific is home to roughly 4 billion people, or nearly 60% of the world’s population. In recent decades, Southeast Asian countries including China, Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong have experienced periods of rapid economic development. Even so, many Asian countries still face high levels of poverty; about 1.8 billion people in the region live on 2USD or less per day. A resulting lack of infrastructure and resources makes countries of the region highly vulnerable to shocks caused by natural disasters and extreme weather.

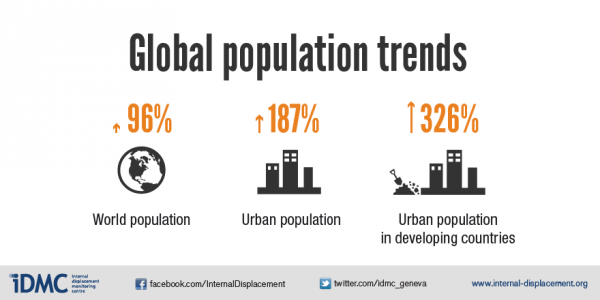

Increasing global trends of population growth, urbanization, and settlement in and migration to coastal areas put more and more at risk of cyclones and other extreme weather events. As underdeveloped countries face these challenges, their progress towards economic development and sustainable growth is threatened. According to head of the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery Francis Ghesquiere, “Large-scale natural disasters, particularly in fragile and developing countries can set back years of development achievements,” making weather patterns a key concern for development initiatives today.

World bank reports estimate that the number of people directly affected by tropical cyclones, specifically, has tripled in the last 30 years. In this time period, cyclones have killed over 400,000 and affected another 466 million people, with their effects falling disproportionately on underdeveloped areas of Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific.

As global population continues to grow and an increasing number of the world’s poorest are affected by climate variability and hydrological extremes, attention to extreme weather and those it affects is increasingly important.

Drought plagues East Africa

By Harland Dahl

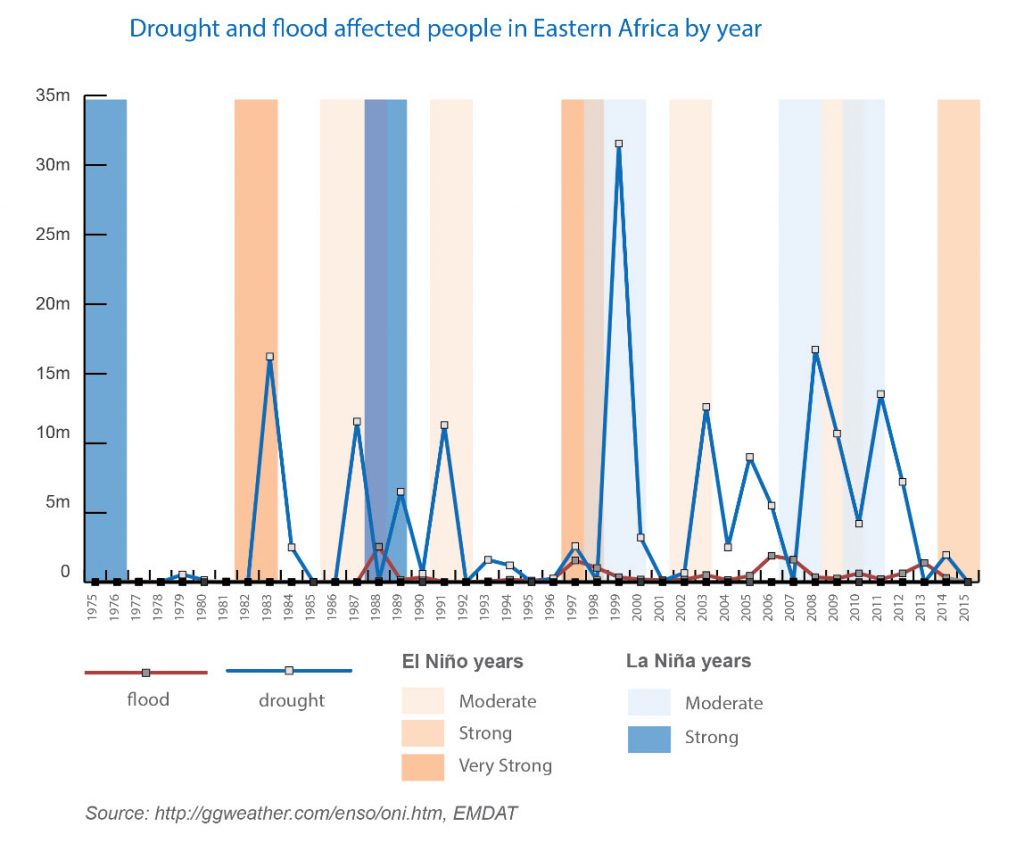

Today, East African countries face a major famine following the worst drought in half a century. Rainfall shifts caused by El Niño warming of ocean waters across the central and east-central Equatorial Pacific are thought to have contributed to this drought.

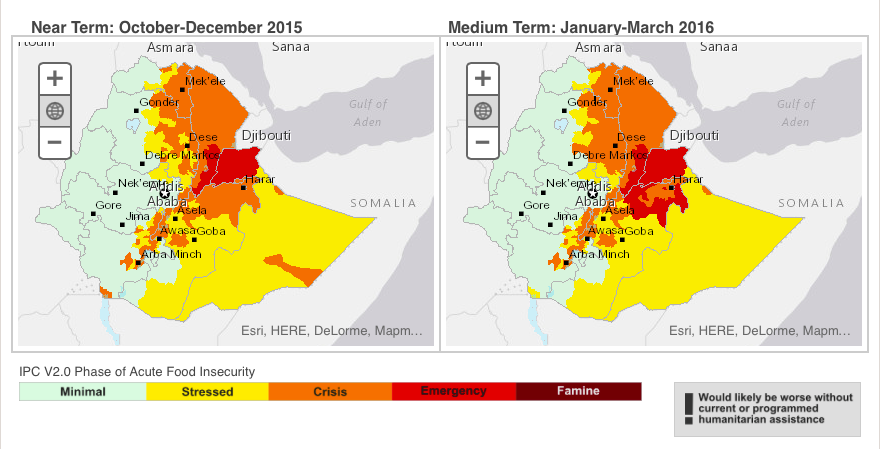

The East African drought has devastated agricultural production in the region, hurting harvests of essential grains and vegetables and killing livestock herds. According to the international non-governmental organization Save the Children, 10.1 million people are currently “in urgent need of food aid” in Ethiopia, Somalia, and Somaliland today. In Ethiopia alone, 5.7 million children are at risk of hunger.

Famine and hunger caused by the drought have been complicated by conflict in the region, and in particular in South Sudan, where violence has made it difficult for non-governmental organizations and foreign aid agencies to deliver necessary assistance. Here, nearly 40,000 people are facing a “phase five” hunger emergency.

According to the Joint Government and Humanitarian Partners’ Document, a joint report crafted by the Ethiopian government and humanitarian agencies working in the country, roughly $1.4 billion in funding will be necessary to address the crisis in Ethiopia, alone. In January, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) pledged $97 million in emergency assistance to this cause.

United Nations agencies working in the country are also feeling the strain of insufficient funding. The World Food Program has estimated itself to have just five percent of the funds necessary to support a full program in the country. These programs are crucial to the survival of many Ethiopians, 80% of which rely on agriculture to survive. In fact, the Ethiopia Humanitarian Requirement Document estimates that current food stocks will be exhausted by the end of April this year.

Drought conditions have been exacerbated by climate change and El Niño weather patterns in the past year. According to a study conducted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, temperatures in most areas of Africa have risen by nearly one degree Fahrenheit in the past fifty to one hundred years.

Temperatures are projected to continue to rise throughout this century, further disrupting weather patterns and bringing heavy rains and lasting droughts to different regions of the world. Research coming from the University of California at Santa Barbara suggests that these raised temperatures could be responsible for an 11% reduction in East Africa’s 2014 April-June rainfall.

The IPCC has warned that this increase in temperature could lead to a 20% loss in cereal yields in Sub-Saharan Africa by mid-21st century. This loss could have a significant economic impact across Africa; according to World Bank estimates, 70% of the continent’s population is employed by rain-fed agriculture.